Carolina Wilcke

Een stille kracht in modern Dutch Design

In de Nederlandse designwereld heeft Carolina Wilcke de afgelopen 8 jaar een indrukwekkende reputatie opgebouwd. Haar werk wordt gekenmerkt door puurheid, modernisme en een diepgaande waardering voor architecturale elegantie.

Met een scherp oog voor esthetische verhoudingen en een streven naar eerlijkheid in elk ontwerp, opereert ze vanuit haar ontwerpstudio in Bussum, waar ze aan projecten werkt voor gerenommeerde merken zoals Spectrum, QLIV, van Esch en Gelderland.

Carolina's creatieve reis begon met een passie voor beeldhouwen en later goudsmeden. Deze ambachtelijke achtergrond is nog steeds duidelijk zichtbaar in haar latere ontwerpen die worden gekenmerkt door aandacht voor detail en sculpturale finesse. Haar formele opleiding bracht haar naar de Design Academy, waar ze zich ontwikkelde tot meubelontwerper. Na haar afstuderen verkende ze aanvankelijk de wereld van collectible design door vrij werk te creëren voor diverse galerijen, maar al snel ontdekte ze haar ware roeping in het ontwikkelen van doordachte, serie produceerbare producten in samenwerking met meubelmerken.

De Palea salontafel is geëvolueerd tot een waar sculpturaal object, wat mijn liefde voor beeldhouwen en de compositie van materialen weerspiegelt

Carolina legt zich vooral toe op grotere meubelstukken, zoals tafels, dressoirs en kasten, en binnenkort mogen we van haar ook de eerste zitmeubels verwachten. Haar eerste samenwerking met meubelmerk Spectrum legde de basis voor haar opkomende carrière en verankerde haar werk meteen stevig in de wereld van Dutch Design. Later ontwikkelde ze een collectie voor het Nederlandse designmerk QLIV.

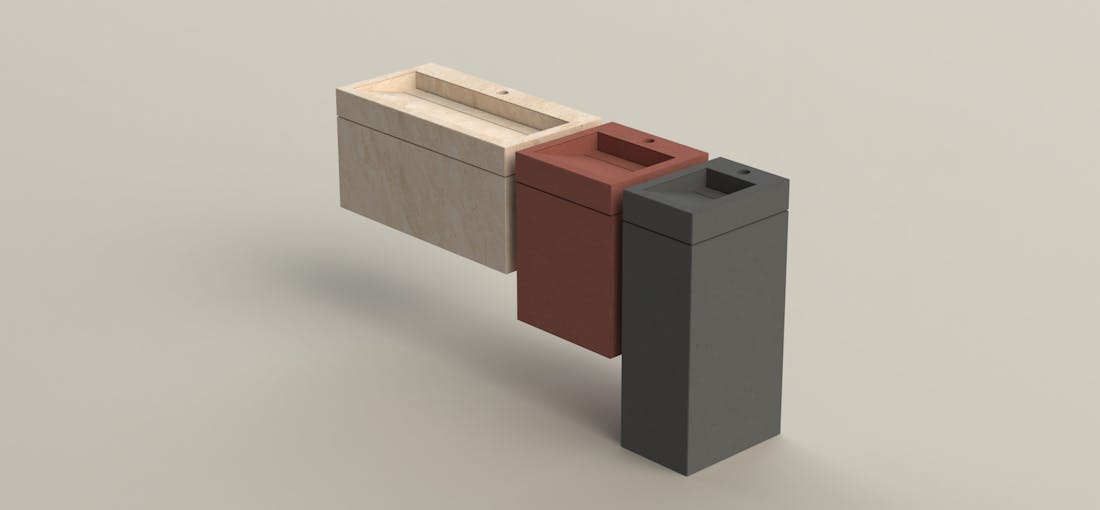

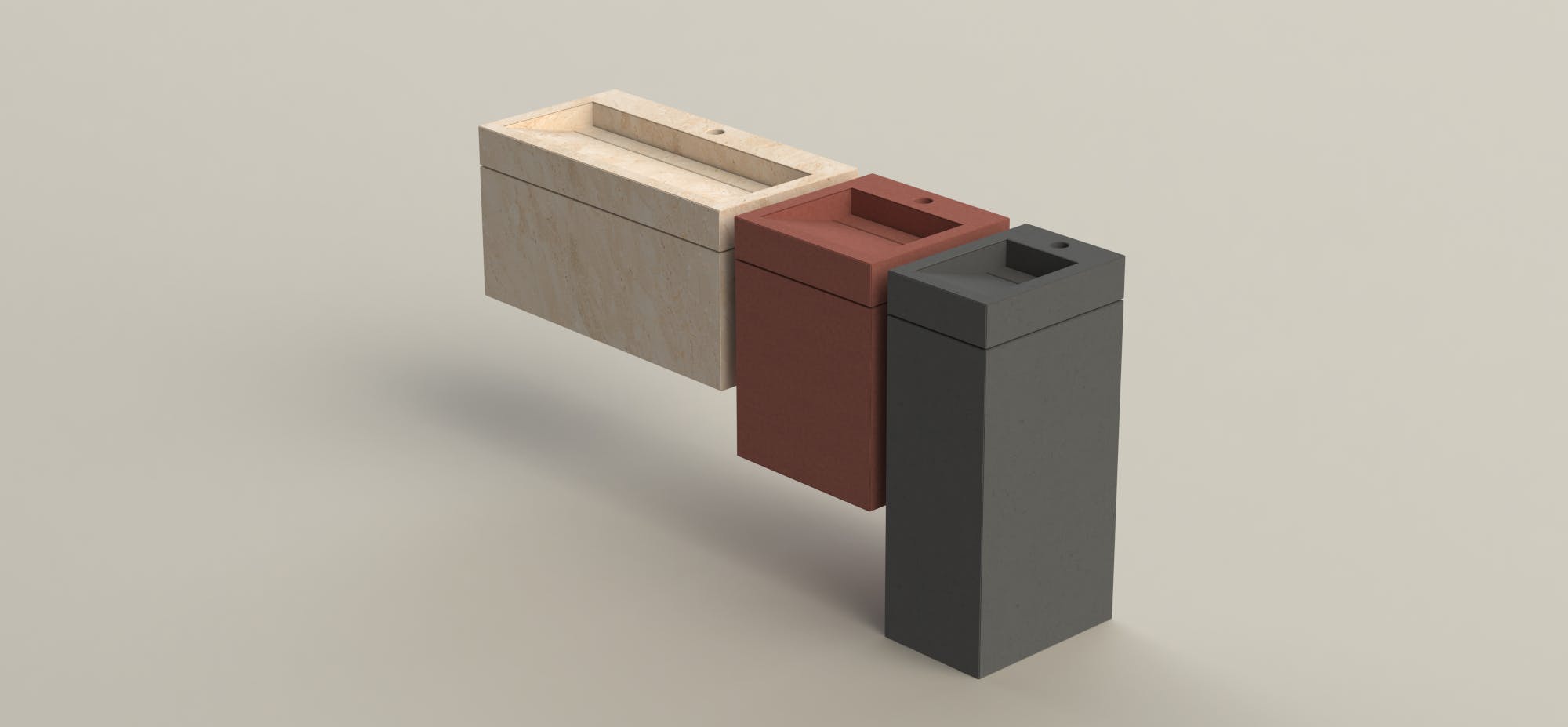

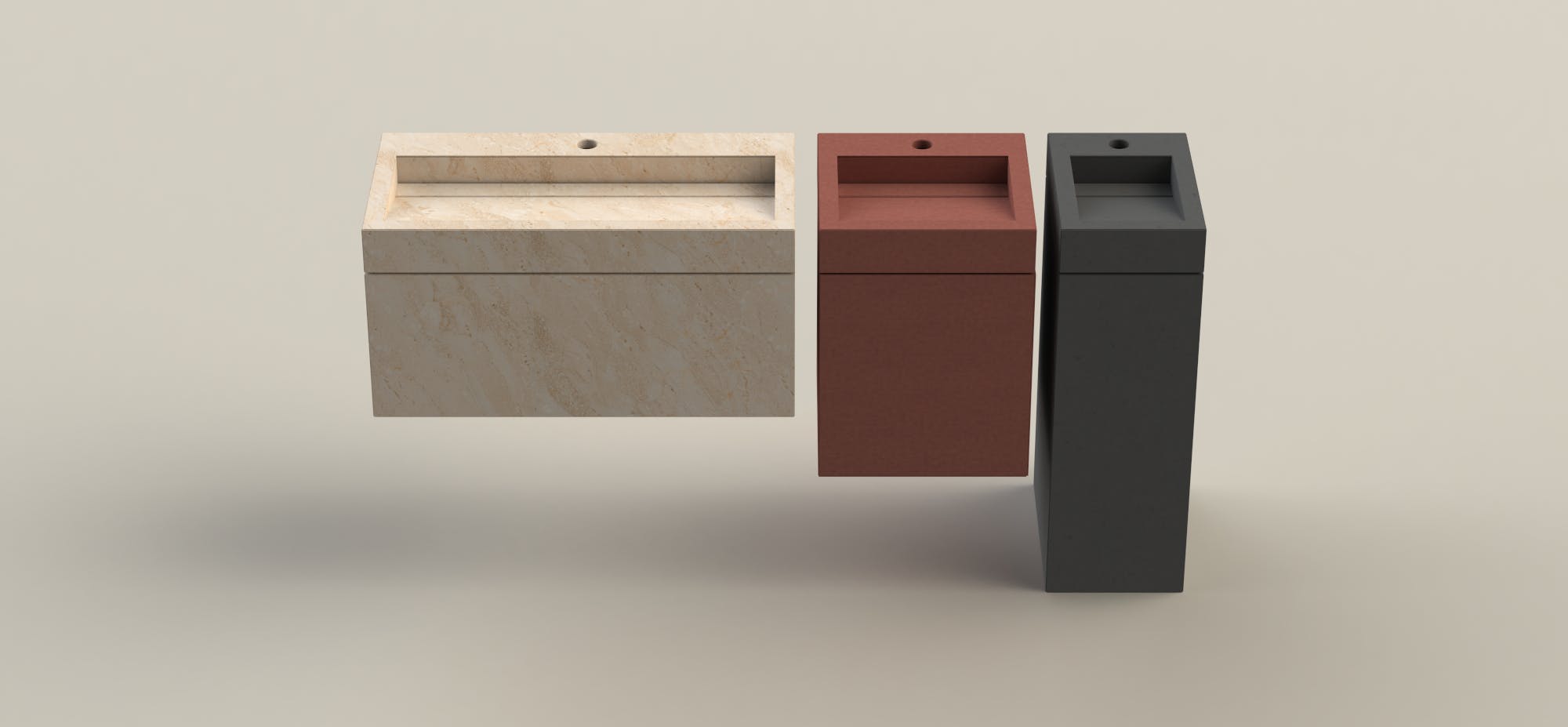

Een van de hoogtepunten uit deze collectie was een salontafel met een blad van Cosentino’s Silestone die voor het eerst werd gepresenteerd op het Amsterdamse design festival Glue in 2022. Dit jaar voegde ze Gelderland toe aan haar portfolio, net zoals Spectrum, een merk van de RSGA groep. Haar meest recente creatie, de Palea salontafel voor Gelderland, heeft veel aandacht getrokken.

De inspiratie voor de Palea salontafel komt voort uit Carolina's diepe liefde voor materialen. Ze werd geïnspireerd door de esthetiek van hout, glas en steen stalen die harmonieus samenkomen in haar atelier. Dit bracht haar op het idee om dit materialenpalet als basis te gebruiken voor het ontwerp van een tafel.

Het ontwerpproces vereiste geduld en experimentatie om de juiste verhoudingen te vinden. Uiteindelijk evolueerde het ontwerp van een groot houten blok als basis naar een subtielere voet in hout met een groter glazen blad en een toplaag van Silestone.

“Ik heb zelf een keukenrenovatie op de planning staan en daarvoor staat Cosentino op de wishlist. Voor keukens is het ideaal, zeker als je graag kookt en kinderen in huis hebt, wil je een materiaal dat zowel mooi als praktisch is.”

Carolina Wilcke is niet alleen gefocust op vorm en functie; ze heeft ook een diepgaande waardering voor duurzaamheid en circulariteit, twee groeiende pijlers in de wereld van design.

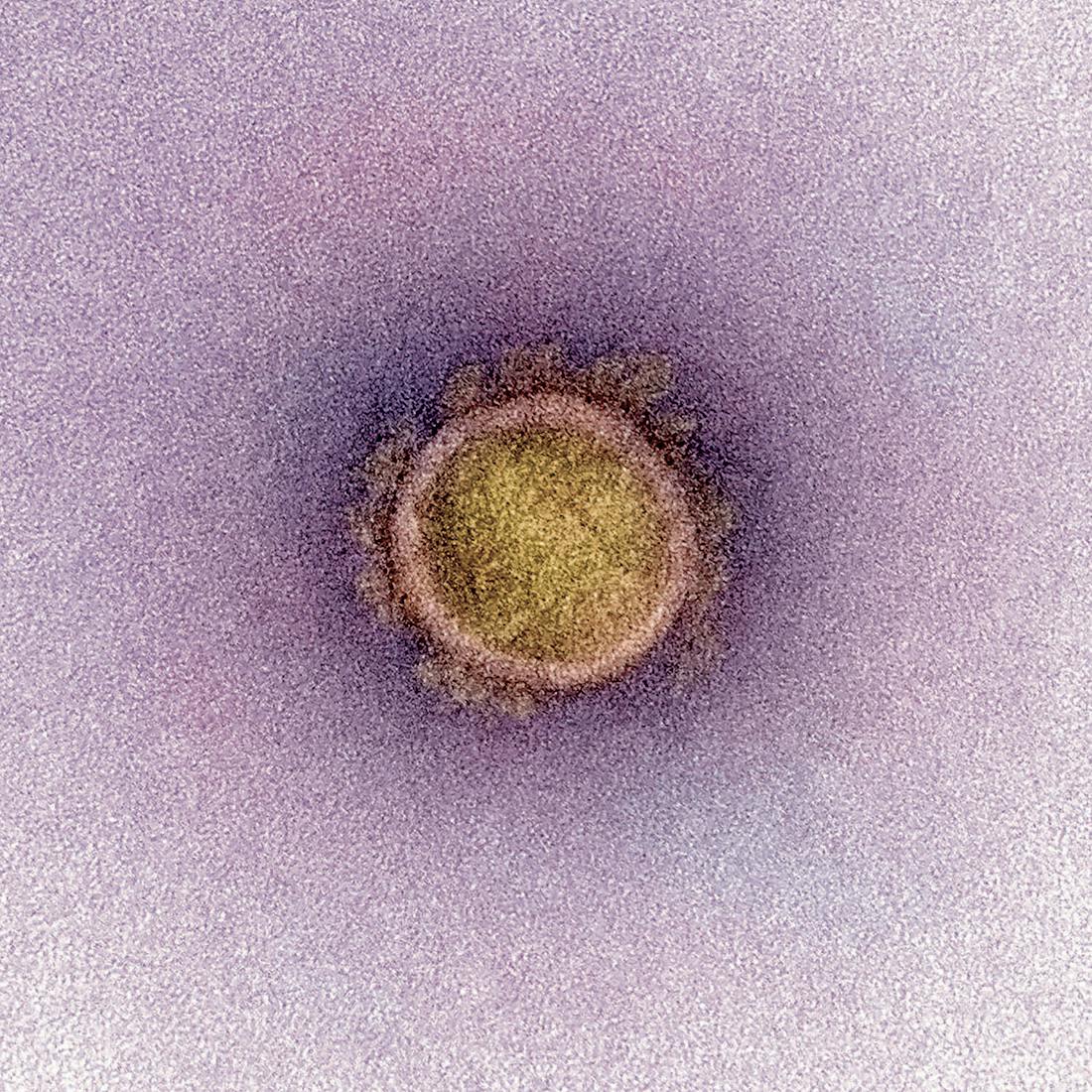

Ze merkt op: "Wat ik interessant vind aan Silestone Le Chic is dat het er zo ongelofelijk goed uitziet met de doorlopende adering aan de zijkant, die cruciaal is bij een ontwerp als dat van Palea; en dat het tegelijkertijd zo duurzaam is."

Dit materiaal van Cosentino biedt niet alleen esthetische waarde, maar belichaamt ook de groeiende trend naar duurzaamheid die de toekomst van design zal vormgeven.

CAROLINA WILCKE

Design